An Interview with Nels Cline: Limitations and Language

One of the great things about Newport Folk Festival is that there are things that happen there every year that will never happen again. That’s part of the point: what can we do in this place together that is unlikely to ever occur again? One of those sets will be Nels Cline leading a band with a set framed around and inspired by a 1937 National Duolian guitar, the sound of which has been described as: “incredible, deeper and less clanky than a typical steel guitar, with each note bathed in a rich, lingering echo.” If you only know Nels’ work in Wilco, good God there is a lot more to know. We got to chat about both this set at Newport and his incredible last album with The Nels Cline 4, Currents and Constellations. This is a set that you want to be at; because it’s only happening one time, friends.

RLR: The set you’re doing at Newport seems like a pretty unique experience.

NC: I’m being a little bit cagey about it because I want to take people by surprise. I’m not an obvious choice for a folk festival. So what the hell am I going to do? I’m going to play some songs. But I can tell you that I’ll play the lion’s share of the set with an amazing guitar, mandolin, and banjo player, Brandon Seabrook. Brandon’s not somebody the folk community will be aware of; his own music is super hardcore, advanced, kind of insane. He has astonishing technique, but also extremely wild ideas. His current project is called Die Trommel Fatale, and there’s a bunch of drummers and him, super hardcore, it’s dark, a kind of post-metal thing. His guitar playing is super spiky and very articulated, but he also plays banjo and I’m enlisting his shocking degree of talent to get me through this, because I’m not much of a solo performer. I do have a special guest that I will not disclose who’s going to be a lot better known to the world than Brandon is. And I might sing.

RLR: The set is framed around this Curtis Rogers guitar–what kind of sounds from this guitar drew you to it?

NC: Tom Crandall worked on it, and it’s quite a story. My initial idea was to try to play songs, that this man Curtis Rogers might have played on it. That turned out to be cowboy songs; he was kind of a cowboy troubadour and so I kind of had to bail on that idea. I’m going to do something more along the country line, rather than cowboy songs. The cowboy repertoire didn’t end up being super inspiring to me, particularly because I want to do some instrumental forays. So, I’m going to mix it up and hope the folk world can handle a slightly more eclectic mix. And a lot of the songs I’m choosing to play have some relevance to what’s happening in the world, and have personal resonance. [Note: you can see some of Tom Crandall’s work to restore this guitar on the TR Crandall blog, here.]

It’s kind of surprising to me that people to this day will say to me, “I didn’t know you played acoustic.” I mean, I play guitar; the chances of me playing acoustic guitar are pretty high. I did start on electric guitar; my dad got a little Japanese electric guitar from a student for $30. But I was in groups, particularly in the ‘80s, where I was playing exclusively acoustic instruments, so it’s not some weird leap for me.

And I am kind of obsessed with resonator guitars, like this dobro that I’m going to play; and I have a few of them that have different qualities. But this particular guitar is very magical. And when I saw it hanging on the wall in TR Crandall, there was no reason in hell that I should have bought it. But, of course, it was calling to me visually. When I played it, fascinatingly, or sadly, it’s the most amazing sounding guitar. So besides its haunting visual appearance, it’s an incredible sounding instrument and because Tom worked so hard to restore it, it plays perfectly.

The only challenge was to come up with something that honors the Folk Festival and my presence at it, but also something that’s personal, that has something to do with me. To be honest, my first impulse was to try to fit into some other kind of narrative that’s really not as personal, it’s just maybe more iconic folk. And I know that Jay Sweet really loves Elizabeth Cotton and I know he’d love me to do an Elizabeth Cotton song, but I don’t really play that style; and so potentially there is something almost disrespectful about me attempting that. So I started thinking more along the lines after my investigation into the cowboy repertoire and thinking about the legacy of folk music and the Festival, I started thinking what the hell do I do that fits into this?

RLR: I read an interview with you where you alluded to the idea of creating a language in the different groups you’re a part of, whether that’s the Nels Cline 4, your duo with Julian Lage, or Wilco–how do you think about that in this kind of setting, where it’s more of a one-off, but also can you talk a little bit about what goes into developing that language and what you’re listening for to see if you’re there with other folks?

NC: Jay Sweet specifically asked to me to play an acoustic set, so that itself became a defining element and a limitation, and I don’t mean “limitation” in any sort of nervous or pejorative sense. I really thrive on these kinds of limitations, because it helps me define what the language is going to be. I have a lot of cool guitars, and I thought in this case that this Curtis Rogers guitar is one that I should by all rights not own, because I’m not a fingerstyle or country blues wizard. But the guitar, besides having this astonishingly gorgeous, weird incredible appearance–the patina is super distressed and there’s a painting of Curtis Rogers’s wife on it–it sounds completely amazing. The delight of this will be to express myself however I can manage to with this instrument, and the instrument in this case will be a defining element, if not the defining element, from my standpoint.

With a group like The Nels Cline 4, or the duo with Julian, it was sort of a given straight away that we would eschew effects pedals and distortion and all that stuff. We started out playing together acoustically, just the pure sound of the guitars was enough and the way that [with] the improvised occurence of a polychord that, we can pause and savor, which is one of the great things about how we play together, the ability to listen while we’re playing and hear something that sounds amazing to us and just let it hang in the air that the straight sound of an acoustic or electric guitar is enough.

Since the duo record, Julian’s obsessed with telecasters, and his sound has changed over the last few years. He’s got a little grit in there. And with the rhythm section in the 4, there’s a little bit of hair on the tone. So there are a couple little distorto, overdriven tones, but once again, I elected to eschew looping, heavy distortion, or tons of delay that I do with The Nels Cline Singers, or with my wife Yuka and our duo, cup; or the duo I’m doing with Scott Amendola now called Stretch Woven, which employs as much stuff as I can bring. That language, that is, to the language of looping and harmonizing and modulation effects, the inspiration for that came from listening to studio-created music: Jimi Hendrix particularly, but also studio effects such as phase shifting, and delay, and panning.

I found I had this ability to imagine sound based on what an effects pedal can do. People have asked me how I come up with this stuff, and it was never part of the plan, but my ability to imagine it has something to do with listening to psychedelic music when I was young. A song like, “I Had Too Much To Dream Last Night,” by The Electric Prunes, or “Happenings Ten Years Time Ago,” by the Yardbirds are sort of miracles of engineering in their day. And they have a lot going on sonically and textually, not just harmonically or melodically.

And I’ll use objects on the guitar, not as many as I used to–I’ll use a spring or a bottleneck and much of that’s inspired by Fred Frith in the ‘70s, his record Guitar Solos and subsequent things he’s done–his whole guitars-on-tables phase. He uses a lot of different objects to play the guitar and detunings; so he’s an influence in that way. And Sonic Youth are a very important influence on how I hear electric guitar. But I’m not using those sounds to be novel; I’m just hearing them in my head, and the electric guitar is really malleable and I can expand the expressive capabilities and the sonic potential of any given moment, using effects pedals and all that stuff. But I never thought, “I’m going to be a guy who uses effects pedals.”

RLR: I’d love to ask you to go into the process for a few tracks on the record, and if it’s all right, I won’t say that much about them, and just let you talk through their genesis and evolution.

NC: Sure.

RLR: I’d love to hear about Imperfect 10, which covers a lot of ground in a relatively short amount of time.

NC: “Imperfect 10,” was kind of an accident. I kind of wrote this song while on tour with Wilco at one point. I don’t often have the ability to multitask; usually on tour, I just kind of do what I’m doing and don’t write a lot of other music. But I was just screwing off playing in the dressing room and I thought, “How about if we try this,” even though it was pretty far, stylistically, of what I was thinking what NC4 would be. Temporarily, by Carla Bley, is closer [to what I had imagined]–kind of an electric band with some electric energy, but also more of an improvising chamber jazz kind of thing. So here was this kind of groovy, odd-meter vamp tune that sounds like something that John Scofield might have written. And I thought, “This is going to be a little limiting,” and it’s the only song where I thought Julian will play solo, then I’ll play a solo. We don’t do that in this band much. It seems to be for a lot of people a stand out track; and I think that’s because it’s accessible, it’s got a groove, it’s got solos and it’s kind of playful.

NC: I can go programmatic, but I wasn’t thinking programmatically on “Furtive.” The title came after the song, as opposed to, “Swing Ghost ‘59,” where the title came before the song. That’s pretty rare in my case; usually coming up with titles is just a big headache. “Furtive” sounds like it could be some kind of car chase, but I was really thinking about a piece by Duke Ellington, called, “The Tourist’s Point of View,” from the Far East Suite, and wanted to have kind of an uptempo, spangalang cymbol kind of groove and vamp and explore polyphony with the two guitars, which is one of my favorite aspects of playing with Julian–the ability to layer harmonic content in a dense way that to me sounds beautiful, but I know is kind of dissonant to most ears. It’s intentionally so, and there’s kind of a clanging that you can get going that’s almost like metallophones. And that song is really just an attempt to investigate, with just a few musical ideas, that terrain. And then to interact with Julian in a non-soloistic way; just to get counterpoint going, and a dialogue. It was actually Julian’s idea to start the record with it. I had a different idea of how to start and I’m really glad he suggested it, because just starting a record with a Tom Rainey drum solo is my idea of a good time.

NC: When we play it live, it’s longer. Initially, I recorded about half the record, just to see what it would be like to record with everybody. There was no Blue Note deal, there was just this band and we’d done a couple of gigs in a row, and I just thought, “Let’s go in the studio and try to record some stuff.” And some of the stuff we hadn’t even played live, we just learned it and recorded it. A song like, “As Close As That” is an example of that.

I gave the rough mixes to Don Was to listen to and he loved it. So the next thing I know, we’re actually making a Blue Note record. Like Lovers, these records are just licensed from me, and you see the little label from my label, Alstro, on there.

I had a limitation because Blue Note said it had to be a vinyl length release. When you’re doing vinyl, as I’ve done a lot, and sort of mixed emotions about in its current revival, which is why we buy carbon-offset credits for our vinyl releases. I’m trying to start a trend; this was my friend David Breskin’s idea initially. With vinyl, you have this conundrum of side-lengths, and it has to fit to be properly masterable. My previous releases tend to be too long. So, overall, it was probably a good thing to be forced into a more truncated format. But it necessitated that “For Each, A Flower,” which really Julian and I had just done as a duo, be on the record in a shorter form. And it’s fine to be super short, because I wanted a poignant coda.

The piece is very minimal and was written when I was mourning the deaths of many people all around the same time, most of them musician friends or acquaintances: people like Bill Horvitz, the guitarist; Bill Collings, the luthier of Austin, Texas; John Abercrombie; bassist John Shifflett; my friend Don Waller. All these people passed away within months of each other. Most of them were close to my age, or just a little bit older. So it was pretty sobering and I was mourning and I wrote this piece as a tribute to each one of them.

RLR: It’s a wonderful tribute.

NC: Thank you.

RLR: This question is a little tongue-in-cheek. Langhorne Slim was doing this thing on twitter that I loved, where he’d tweet a song title and then write, “best song ever.” I loved it for its joy about music and also kind of flips the canoe on “best ever” lists anyway.

NC: Oh, yeah. How many times have I been asked: “Who is your favorite guitarist?” or “What’s your favorite song?” It’s not possible, it’s not even human, to answer that.

RLR: Yeah. That’s what I love about it, because it’s an ability to express unapologetic joy without having to rank stuff. So, with all that said: for you, now, what’s the best song ever without explanation or apology?

NC: … Jade Visions. I can stand behind that any day.

I know where I’ll be on Sunday at 1:30 – right up front at the Quad stage to get a look at this Curtis Rogers guitar and to hear its sound clear as a bell. See you there.

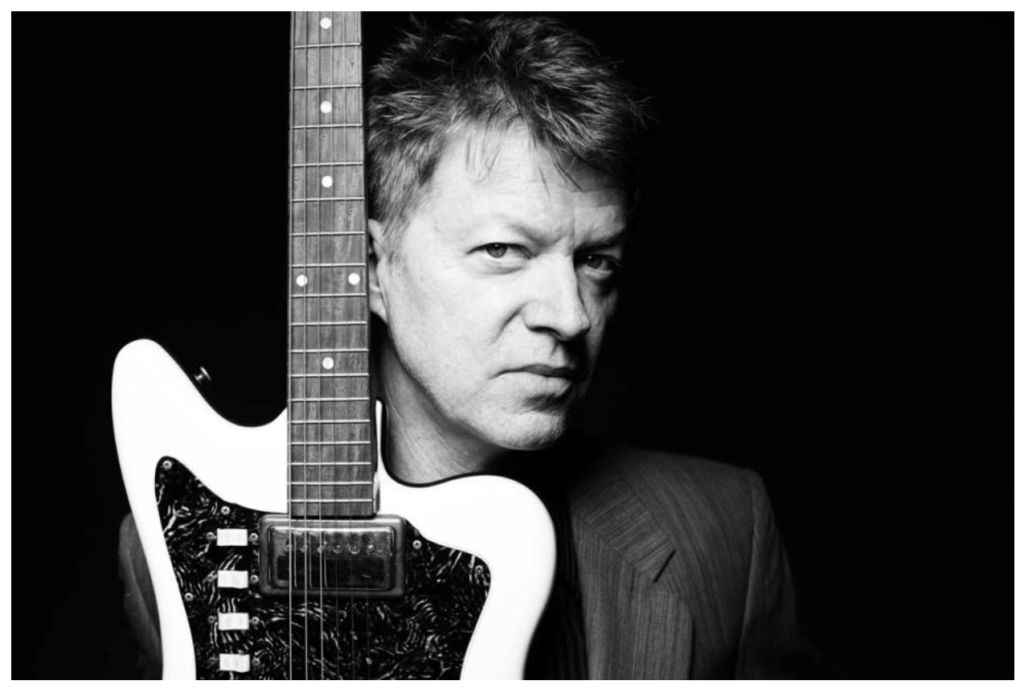

Photo Credit: Nathan West