An Interview with Mark Erelli: Something I Love

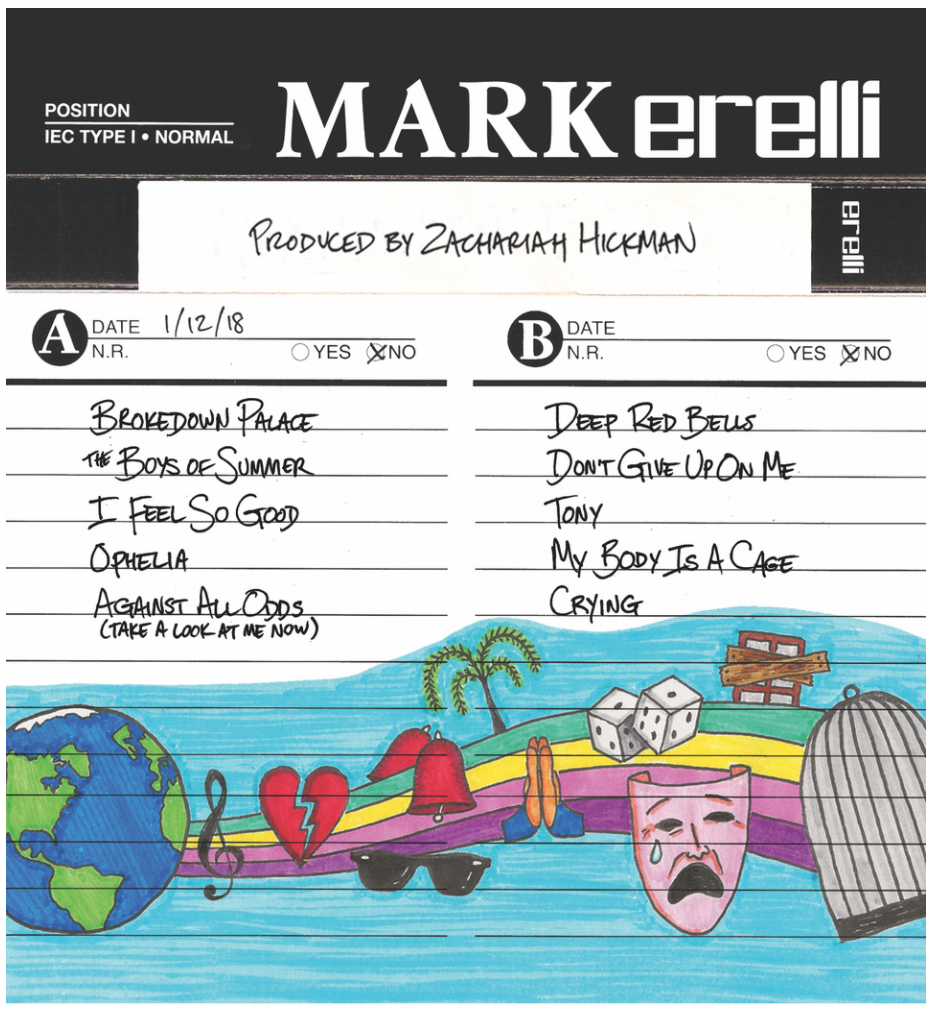

Mark Erelli just gets better and better. His last album, For A Song, demonstrated incredible craftsmanship and lyrical quality. He’s back with Mixtape, which will be released on January 26. His release show at City Winery is already sold out. Mixtape is a covers album that grew out of the longstanding “Under the Covers” show at Club Passim. It’s a really diverse set of songs and Erelli’s vocal range is on full display, covering a wide variety of artists, including Phil Collins and Richard Thompson, Patty Griffin and Solomon Burke. We got to chat with Mark about the album and what makes a cover song great. This album is fantastic and you should grab it up.

RLR: Can you talk about what inspired this project?

ME: Every December for the past thirteen years I’ve done a show at Passim with some friends of mine called “Under The Covers.” We play different cover songs, and it could be anything from Sir Mixalot, to the theme from Star Wars, to Joni Mitchell or Randy Newman. It’s all fair game. And I’ve always thought I would do a covers record, drawing on the material I’ve approached each year and finally got around to doing it.

RLR: What has that experience of putting on those shows taught you about the art of a cover song?

ME: I’ve learned a lot about myself from cover songs, mainly where my limitations are as a songwriter and a singer and an artist. You have patterns that you fall into for your own material; cover songs give you the chance to step inside someone else’s head and their artistic vision for three or four minutes. And, not surprisingly, other people’s artistic visions are different; they’re not limited to certain chord progressions, or keys, or lyrical ideas, so when you cover their song, you get to feel unshackled. I feel like I’m running off leash when I cover a song, there’s a whole new world for me that I didn’t know from my own little doghouse that I’ve built around myself.

RLR: I can imagine there are other folks who would view a cover as constraining.

ME: There is a school of thought that you just play the song as closely to the way the original artist did … and I don’t ascribe to that school at all. When I cover a song, I only listen to it [enough] to remember the lyrics accurately. Unless it’s a Beatles song. You make an exception for the Beatles, because you’re not going to improve on that. But anything else, I really don’t want to dwell too long on how it was originally done. I look at a cover song as an opportunity to create something new, not rehash something that’s already been done. I don’t even want to do that for my own material.

RLR: You have said that not one of your friends has known the origins of all the songs on Mixtape.

ME: I was kind of surprised by that, as there’s no one really obscure that I’ve covered here. But maybe this record will turn people on to new music they haven’t heard before. It just reminds me of one of the more innocuous purposes of those old mixtapes we used to make: one simple purpose of those was to let somebody know, “Hey, this is music you might not know, and it matters to me.” You want to be seen with that mixtape. You can choose the music such that what you’re really saying is you matter to me, or that summer was the best summer of my life; so you can telegraph these coded messages. But the most basic one is “this is music I love.”

RLR: I wondered if that was deliberate to have this balance of artists and songs that would be immediately familiar and those that might be less obvious to listeners.

ME: It was. I can cover some pretty obscure shit, but if the only reason people know it’s a cover is that they’re at a covers show, it’s not very effective. You want there to be those three or four bars at the top, where if you’re changing the song, that people are searching their mental rolodex, and then the first lyrics come in and you can feel the recognition in the crowd. So you don’t want to get too “inside-baseball” with your choices; that’s why I went with a mix of megahits and just great songs.

RLR: There is something about a really good cover song, that when you’re at a show and one of your favorites starts to play a cover that the crowd kind of surges in a different way—what do you think that’s about?

ME: All of us want our music to be part of this shared cultural experience, but the way we consume entertainment and art and culture these days, that’s really hard to accomplish. We’re all fractured, and tuning into algorithmically programmed streams and podcasts and programmed mega-radio stations. Sometimes it seems like the only way to have those cross-genre, cross-generational experiences is through a cover song. And I don’t actually cover that many songs in my usual live show but the encore is often a place where I’ll do that. I’ve been using “Crying” and “Don’t Give Up On Me,” both of which are on Mixtape, as encores for years.

I was opening for a certain female artist, and I was playing with her, and I thought her audience would accept me, because she accepted me and I was in her band. It was a largely female audience, and they were just not getting me at all, they couldn’t figure out what this dude was doing there until I covered a Joni Mitchell song or a Patty Griffin song, and all of a sudden it was like, he has some familiarity with this community and the artists that mean something to us. So, like I was saying before, you don’t want to do anything too obscure, because you want that connection across time, across genres, and across audiences.

RLR: How much of you was thinking about songs for this project and how much of you was thinking about artists that you wanted to cover?

ME: It went back and forth. There’s people like The Grateful Dead, where no one looks at or listens to me and thinks, “Man, he must have been a huge deadhead,” but I was. To me, they were a gateway band. So much of their sets were traditional songs, bluegrass, country, or early rock and roll. I’d listen to these old bootlegs, and think, “Which one of them wrote “Cold Rain and Snow?” and find, none of them did, it’s a traditional song,” and there is this vast swath of American music that I found through the Grateful Dead. So, it was like what song of theirs can I do something with? And I’d always heard “Brokedown Palace,” in the stately, mournful way we do it on Mixtape.

As for Richard Thompson, “I Feel So Good” was the first song I heard by him, and I can’t understand why everyone doesn’t know this song. It is a perfect and kind of humorous song, with a lot of great energy. I really wanted to show how much there is in a Thompson song; it’s not just guitar, which is what he’s known for. But he’s an amazing songwriter, and when you have an amazing song, you can do it almost any way and it’s going to be fine. The approach I hit upon was, “What would it sound like if Al Green was covering it?” So it’s a little restrained and then opens up and there’s a sweet falsetto that works at cross-purposes to the nastiness of the lyric. For me, that was a way into doing a Richard Thompson song that didn’t have to be this guitar facsimile. It feels like a whole different thing.

So it was highlighting certain songs and certain bands, and also highlighting certain times of my life. I don’t listen to a lot of 80s music now, but at the time, I was glued to MTV. I grew up with that stuff, so it’s in there whether I want it or not.

RLR: You mentioned this in the kickstarter video, that some of the 80s songs get a really new treatment. And I feel like the approach to production in the 80s obscured some of the lyrical quality sometimes.

ME: Definitely each decade has its own production aesthetic, as far as popular music. Some of the production holds up, but a lot of it is pretty insufferable–you know, any time the electronic drums start coming in, or those horrible gated snares. There’s some great synthesizer stuff, but there’s a lot of cheesy synthesizer stuff too.

So the 1980s stuff was sort of ripe for liberation–not so much, “Boys of Summer,” because I still really love that track, but my interpretation grew out of the guitar parts. I love the guitar on that song, which suggests a darker, more organic sound.

But the Phil Collins cover is probably more of what you’re talking about, because that’s really changed. [We choose] our songs all year long [for the “Under the Covers” show]. We’ll send each other texts here and there, saying, “Hey you should do this song, you’d kill this.” I got a text from Zack [Hickman], saying, “Against All Odds. The production’s hard to listen to, but that’s a great song at its core and you could slay that.” So I took it as a challenge, you know, and I did it by changing the time signature, and the feel, and then it was Zack’s idea to bring in the strings. So, the production can be a box that you need to liberate a song from. If you listen to the Phil Collins track, it definitely brings you back to that time. The way I did it, it could almost be an Otis Redding song; that’s the way that I heard it. It’s really fun when you can reinvent the song with your cover in a very respectful but effective way.

RLR: For any of these songs, as you started to work on your arrangement, did you uncover elements of the song that you didn’t expect or see until you started working on them? Or did another player on the record, or Zach Hickman as the producer, show you something you hadn’t noticed before? I love the little call and response between you and Sam on “Brokedown Palace,” for example.

ME: I love that you singled out that on “Brokedown Palace,” because that was my idea; and I was like, “I hate to tell you what to play, Sam, but can you kind of twinkle on the ivories this way?” Sometimes I’ll hear something specific and make my desires known, but in general, I try to hire the right people that I love and respect for what they do and just let them do that thing.

I produced my last two records; Milltowns and For A Song were my vision, and I was really grateful to be working again with Zack as a producer. There’s a lot of logistical things to pull together, but he also just knows more about music. He can hear things, and can say, “We should do it in this key, because it’ll be easier for the strings.” I mean, I would never think to use strings, because how could I make that happen? But Zack wrote string arrangements, and conducted in the studio. There are moments where he will assert a certain kind of vision but those are actually fairly rare because we’re working with people that we have a history with and it’s usually at most a suggestion. Like, maybe the drums don’t come in until the second verse. We said that to Ray Rizzo, the drummer, for Brokedown Palace, and so he began by just snapping. And I was like, what the hell is this? And you can hear him pick his brush up, because he didn’t do it quite cleanly, but he does it in time. And I love that sort of stuff, when people make those decisions or happy accidents, because Zack gives them the freedom to make their own choices.

RLR: Something I love about this project is how much it reminded me of making mixtapes. And waiting for a song to come on the radio and having my boombox with my fingers ready on both record and play –

ME: And the record button wouldn’t go down, yes. It does highlight just how far we’ve come in how we consume music. It does bring us back to that time, when it had to mean more to you because there was only one way to get it, and it required prep, and forethought, and focus. I do think we’d be better off if we figured somehow to merge the bounty of digital streaming with the focus and intention with which we used to listen to music.

Part of what I hope for this record is that through doing other people’s songs, people might ironically get to know me better. Even the album artwork–I used to do that on my mixtapes when I was in high school or junior high. I sat down and started doodling, and an hour later, I felt like I had been fifteen years old for that hour, just transported back to that time. It’s that striving for connection, not to just be known by who I am now, and what I can do know, but kind of where that comes from. The artist I am now didn’t just happen; I wasn’t this artist when I started, I had to grow into it. It started before I was even playing music, back as a fan, so this record gives people a sense of that trajectory.

I was hoping beyond the nostalgic medium aspect of it, that it would make people nostalgic for the kind of music they used to put on mixtapes and the music they love. In that way, it’s a tribute to being a music fan, and I need that in my life too. It’s a reminder that this is something I love.

You can order Mixtape and hear some tracks at Mark’s bandcamp page. We previewed the album back in the fall with Mark’s great version of “Ophelia,” so check that out too. And while the City Winery show in March is sold out, Mark has a run of shows in March after he finishes touring with Josh Ritter and you should be there too; tour dates here.

Photo Credit: Lara Kimmerer