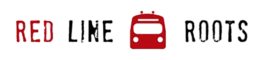

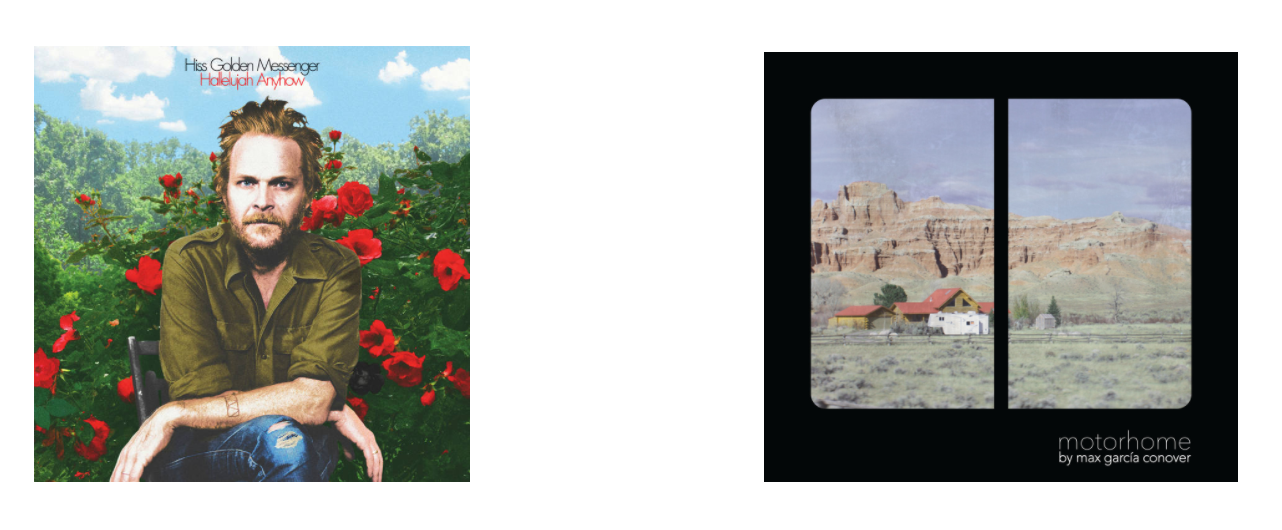

Tiny Fires in the Darkness: Hiss Golden Messenger “Hallelujah Anyhow” and Max García Conover “Motorhome”

My two favorite songwriters are releasing new albums on Friday: Mike Taylor (Hiss Golden Messenger) and Max García Conover. It isn’t the coincidence of dates that makes me write about these albums together; it is the thread of warmth, community, and vulnerability that runs through them both. For Taylor, that community swells and retracts like breathing. For Conover, there is more a sense of seeking a place to shape into a home that I think is, for many of us, reflective of what it means to grow up and really know yourself.

Motorhome begins with a sense of and dislocation, dissatisfaction and restlessness that propels “New Sweden,” the first song: “Wasn’t this, wasn’t this, wasn’t this supposed be temporary, just to pay the bills a bit?” Conover wrote the song on a pizza box in Stockholm, Maine on a break during a marathon set at Eureka Music Hall and it reminds me of the humor and frustration in “Maggie’s Farm.” Conover sings: “In New Sweden, there’s a man I know, / And he makes his money working for rich folks, / And he says, the sun only shines on them.” The tempo alternates between lulling fingerpicking and breakneck strumming, setting a tone for the album: the songs shift and grow, expand and contract. Culminating with the line, “Honey, I won’t wait for the sun anymore,” the song sets us up for the album’s thematic searching for place and purpose. It segues well to the next track, “Grand Marquis,” a tapestry of memories, orbiting around the chorus: “My lady put a lot of weight on the pedal, riding home in the light of the stars. / We knew good love and we knew it ‘cause we never called it ours.” The song is a good example of Conover’s ability to slip little adages into his stories that help reset your perspective: “Scared money don’t win. / Scared hearts don’t love.” Those are lines you earn through lots of paring down to only the words you need, allowing plenty of space for the listener.

The album’s title track references an actual motorhome that Conover and his wife Sophie Nelson bought in 2014 to tour the US. “If we make it back to New York,” Conover begins after a thrumming finger-picked introduction, “We’ll tell them all about New Mexico. / Thanksgiving in the Wal-Mart parking lot / Transmission busted on our motorhome.” Suffice to say, the doubts that some friends and family expressed about the suitability of the vehicle came to pass. But of all the experiences Max and Sophie had on this trip, perhaps the most salient is expressed in the song this way: “We stopped asking everyone’s permission / And we found out it wasn’t theirs to give.”

This is an album about knowing yourself and being true–two essential elements to finding home and community. In some cases, this is about the connection between you and one other person. This comes across most beautifully on “Abigail For A While,” which features Nelson on backing vocals and Ben Cosgrove adding an understated piano accompaniment. “You remind me of seventeen, the lot where the snow drifted high. / You remind me of deer season stillness, your father out late every night. / You remind me of tiny fires, cold hands and loose tobacco. / Leaning in close to block the wind, you remind me of first match glow. / I’ll believe in anything for a while.” Conover’s ability to write the telling detail and to keep things spare is notable and reflects a certain confidence to resist telling the whole story. He comes by this skill through both creative talent and through dogged work: he’s released over sixty songs in the past eighteen months through his patreon project. To paraphrase John Dufresne, the first rule of writing well is: ass in chair. Many of the project’s next iterations are on this album, with changes to lyrics and arrangements refined over time. There are many, many fine songs in that collection, and I encourage you to spend some time with those songs too.

What I appreciate about Conover’s writing is that while the subject matter is serious and the songs are carefully crafted, he does not take himself seriously and there is plenty of wry humor on the record. In “On The Street After The Show,” a songwriter (maybe Conover, maybe not) finds himself dodging the assumptions an old friend makes: “You said you’re proud of me, that I’m driven by a passion / But mostly I don’t feel that way, and if I’m driven by anything it’s caffeine.” The kind of self-deprecation that runs in these songs is unique, and hard to do well; John Prine and Josh Ritter are really talented at this, and Conover is right there with them. On “Self-Portrait, Part One,” Conover sings a sort of autobiography: “I was a white-looking kid from a small, white town / With a Puerto Rican mom and I thought a lot about how fated everyone around me was. / I was a socialist and a shy little dude, I was playing Tupac in a Subaru / And I married the first girl I ever loved. / I’m not smooth and I’m not tough…but I thought I was.” Conover’s skill as a finger-picking guitarist is undeniable and he is able, with mostly just his guitar and foot drums, to capture a rhythmic intensity that draws you in.

Turning to Hallelujah Anyhow, what ties these albums together for me is a warmth and openness in sound and spirit. From beginning to end, Hallelujah Anyhow feels like a call to community, in the smallest and largest senses of that word. All our communities are, of course, made up of the relationships we cultivate; the darkness and light that thread through the album are reflective of our country and of our individual selves. The album begins with the brightly strummed guitar and bouncy rhythm of “Jenny of The Roses.” The first lines let you know where we are: “I’ve never seen no wages of war.” This stance is less political than personal–within a few lines, the song is more about how to live each day: “I’m gonna be a free roaming dancer. / I followed you, babe, I was looking for the answer.” The image of roses crops up from time to time on the album, most explicitly on the first and last songs and it makes me think not of the duality of roses and thorns, but rather of the idea that the world is a garden and what it becomes depends on how we nurture it. This is, I think, the ethos that is most expressed by this album: the way you live, what you do, how you love, all of these matter to create a life worth living and they matter in the grand scheme of things too. The album title, alluding to the gospel song, reflects that thread of gospel music: in the darkest times, faith will see you through.

On “Lost Out In The Darkness, ” Taylor sings, “If you love me, please tell me.” So much packed into a simple line–he gets at the idea that many times we knowingly and unknowingly hold back our love; we hide it. In the next breath, he implores, “If you need me, don’t sell me,” acknowledging the risk we take by being vulnerable and open to others. Later in the song, he sings, “If you carry the good news, show me,” underscoring that we gain nothing by holding back from each other. This concept of connection is also evident in “Jaw.” In part of this song, he invokes a sense of generational community: “It’s there in the jawline of my son and my daughter. / It’s the way that I testify ‘bout my mother and father. / It’s the way that I rise, yes, with my partner.” There are these small, lilting runs on mandolin and guitar behind these lyrics, echoing the ties that bind and hold us together. The players making up this version of Hiss Golden Messenger complement Taylor’s voice and rhythm guitar perfectly: Josh Kaufman chooses his spots carefully on lead guitar; Phil Cook’s piano is just joyful. Tift Merritt and Alexandra Sauser-Monnig provide backing vocals with perfect subtlety and timing and you can picture Brad Cook bobbing his head to the grooving bass lines, especially on “Domino (Time Will Tell),” and “Gulfport You Been on My Mind.”

What I love about this album is that the hope it expresses and love it espouses do not come easy. “Harder Rain,” begins: “So you say you want it harder? Like more than you can take. / And I know you want to suffer. I’ve been to that place.” Subtle horn accompaniment on this track deepens the emotional quality, recalling Van Morrison’s albums with horn sections that harmonize and reassure without taking over. The song resolves with an uncertain prayer: “More pain won’t kill the pain, heal me, heal me,” far more powerful than saccharine calls for peace without capturing the work required to achieve it. James Baldwin wrote about love in some of our darkest times as a country, and he defined it this way in The Fire Next Time: “Love takes off the masks we fear we cannot live without and know we cannot live within. I use the word love here not in the infantile American sense of being made happy, but in the tough and universal sense of quest, and daring, and growth.” That’s what this album is about to me: quest, daring, growth and for all the honesty about what it takes, this album is full of belief and hope. Despite being realistic about what it takes to be a full and true person and (to borrow from Baldwin again) “achieve our country and change the history of the world,” Taylor is never cynical. The tools to get there are within us. One of my favorite lines on the album is: “You take all of nothing at all, / And you make it so simple, like ringing a bell.” Even with nothing, we have ourselves, we can create, and out of that come meaning. It is an almost Whitmanesque philosophy–what is the purpose of life? That you are here, that identity exists, that “the powerful play goes on, and you may contribute a verse.” The walls we have built–both literally in the world and interpersonally between each other–will come down. And when the shackles fall, Taylor sings: “What you oughta do is melt ‘em down, melt ‘em down. / Turn ‘em into tools and make a garden on the prison ground. / Turn your chains to roses, child. / Tear it down.”

We are living in a dark time. These two albums have made it lighter for me. Do what you can. Sing like a songbird. Lean in close to block the wind. Go walking two by two. Don’t wait for the sun anymore. Spread the gospel of the jukebox. Tear it down. Hallelujah anyhow.