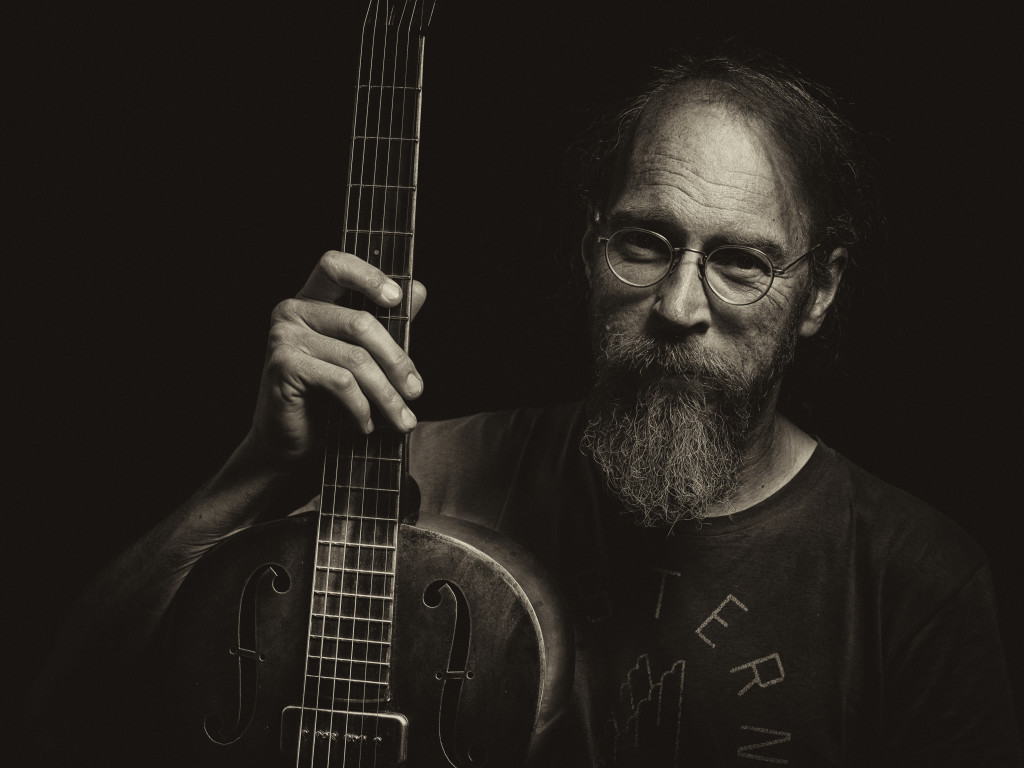

Catching Up With Charlie Parr

Charlie Parr is playing Atwood’s Tavern on November 4th. I got a chance to have a brief conversation with him about his music and his new album Stumpjumper that came out last April. Charlie is an incredible performer, one who traces his musical career back to his father’s record collection of Texas bluesmen like Mance Lipscomb, Lightnin’ Hopkins, and other blues greats like Mississippi John Hurt and Spider John Koerner.

RLR: I read an interview in which you said, “Songs aren’t ever done; they’re in progress” and I wondered how much of that perspective you attribute to the type of music you sort of grew up on, where you can find so many different versions of blues songs, murder ballads, etc. and that is part of the thrill–that there’s always a new way to perform or interpret a song.

That’s reasonable to say. It’s one of the things I got a huge kick out of when I was young. I was a latchkey kid, my dad worked a lot and when he was home, we’d listen to his records. And as a teenager, I was constantly finding these other ways people had done these songs, and it started to sparkle really hard for me. Even now with my own songs, I’ll play a show I’ll hit something differently and the song will change a bit. You think they’re done, but they’re really not.

RLR: How about when other folks might play your songs—there are different feeling these days on ownership of songs than when Lightnin’ Hopkins was playing.

It’s an amazing feeling. I’m honored and flattered if someone wants to play one of my songs. I’m not naturally territorial or competitive. When someone wants to cover one of my songs and they call me up and say, “hope you don’t mind” and I think “Mind? I’m honored.” It’s like you’ve been added into the canon when all you ever really thought about your whole life is music.

RLR: Phil Cook covered “1922” on his new album, which is so good. You’ve said that you recording Stumpjumper with Phil helped you get some songs “unstuck”. And I was amazed that it only took you guys a day and half. Can you talk about that a bit?

I’ve known Phil for a long time. You meet him and you love him and it’s like you never could have felt any other way about him.

I had this group of songs coming out, and they weren’t doing their usual thing. Phil takes things and looks at them in a unique way. I told him I’d been listening a lot to the Spider John Koerner album Running, Jumping, Standing Still to the point where it started to impact me and I couldn’t figure the songs out. Phil had never heard it, so he got it, and it kind of infected him too. So he told me to come out to North Carolina. Just show up, I’ll have some people, kick these songs around. No pressure. I was on tour and I was also obsessed with “Delia” and all it’s weird versions, of which there are a lot.

So I pull into this place in North Carolina and it’s guys just like Phil. They’re enthusiastic and interested. And they’re like me, kind of dumpster divers who live everywhere. No one had heard the songs yet, so they told me to just start playing and they started to play along. In first hour, I had played the record through. It was like showing someone a half-finished painting, and handing them a brush. So then Phil says let’s turn the tape machine on. And most of the songs on the album are first takes.

The only stumbling block was backing vocals because I don’t really get it. But Phil understands it and so he told my wife Emily, “Sing like this” and he sang too. We played it live around a little cluster of mics, then we went out and played show in Raleigh, came back the next day to finish some things up. Phil added it up and said it took us about 14 hours.

He gave me a CD and I listened on the way to Knoxville that night. It was incredible to be able to trust people I’d just met with something so personal and have them treat it with such care.

RLR: One of the things I expected to be different for me as listener with the album was the element of percussion. But I didn’t find that—and there’s part of me that feels like even as a solo artist, you communicate percussion in your performance, even without a drummer.

I’ve never felt comfortable with drummers, because the time is too tight. With old music, especially blues, the time is never tight. It can be painful to listen to old recordings of Lightnin’ Hopkins playing with a drummer at Newport—they’re playing together, but not really playing together. So my immediate reaction is tension with drummers.

But I’ve played a bunch with Mikkel Beckmen, who’s a great washboard player. And he plays not by following the beat, but by following the melody.

One of the huge honors I’ve had was to play with Spider John Koerner. He’s been my hero for so long. His rhythm is kind of like when you throw a wet rug in washing machine. It’s got a rhythm—it’s never right, but it’s always right on. It took me a little while to let my hand go limp and just feel it.

When I play, I have a porchboard and that gives me something like a heartbeat that I can hear, even in louder rooms. I started by using a bureau drawer with a microphone under it, but found this guy in Janesville, Wisconsin who makes porchboards, so I didn’t have to stomp through all my bureau drawers.

RLR: I’m sure you get asked about musical influences a lot. I’m always kind of interested in what non-musical influences you think crop up in your songs. Books, ideas, places, people–does that idea make sense?

I would say I have just as many non-musical as musical influences. Living in the world, I’m kind of a sponge. One of the new songs (“Evil Companion”) is from a conversation I overheard–you know, it was just loud enough that you couldn’t not listen. And that song comes from the spirit of that conversation. I read a lot and am drawn to writers like Raymond Carver or Flannery O’Connor; stories that don’t necessarily have a beginning, middle, end, but are written in vignettes. I just read M Train—absolutely brilliant. I was sad when ended, because I want to know what Patti Smith is doing now. And it’s not really about anything; there’s no climactic moment where Patti Smith slays the dragon. But it had me completely riveted.

There are times when I’m listening to music and it wakes up the environment around me. I’ve been listening a lot to Steve Gunn and instrumentalists who make these textured records. It’s not droning ambient instrumental stuff, but there is a lot going on there—and when I listen to them they change atmosphere of the rest of the world.

When I’m in a mode when I’m open to creating, the opposite happens. The environment around me filters through the music. You know, weather is a controversial topic here in Duluth. Yesterday was overcast and cold and misty and I thought it was a pretty nice day, but I said that to my neighbor and he seemed offended by that idea.

RLR: You recorded your first album in 1999. What has changed and what has been stable for you in the twenty-five years you’ve been making music and putting it out into the world?

I was just talking to a friend about this. I don’t own a computer, so my friend helps me run my website. Our plan is to eventually release everything I’ve recorded on the site.

He asked me to write about the first album, Criminals and Sinners and what recording it was like.

Before recording that album, I had been playing a lot and people would put this big pressure on recording—you know, like: it’s for the ages. But then I met this old punk rocker in Duluth and he convinced me it was not a big deal and he said, “Bring your washboard guy and we’ll record and you’ll be surprised how not a big deal it is.”

So we’re in this gross basement around these old 257 Shure microphones. And he says the only reel he has is thirty minutes at the end of a punk band’s record. We slammed through it, performed it live, and finished the last song as the tape ran out.

Ever since then, I’ve thought of music as moving air molecules around. Even a recording is only what it is on that day. You’re not painting a picture or writing a novel, so it’s not something for the ages. It’s a piece of something from that day that happens to exist beyond that day. And that’s part of why Stumpjumper worked so well, because this “for the ages” idea has always been kind of meaningless to me.

What’s changed is that I’m more willing to add in stuff I might have been frightened about before. I’m more comfortable with myself and a little more courageous—for good or ill. Music is extremely personal to me. I’m happy people like it but if I do something unpalatable to others, I’ll still be happy with it and will be playing it in my kitchen.

RLR: Atwood’s seems to be a venue that you’ve developed a relationship with over the past few years, playing here a couple of times a year. What is it about the venue that keeps you coming back?

When I first came to Cambridge, I played at TT The Bears for Randi Millman and she was pretty much the only person there. But she liked it, she said “We’ll double the audience next time!” So she has been really supportive and the people at Atwood’s are great. The room is great, the sound is incredible, the people who run the place are so supportive. And it’s important to me to be a part of creating a public space—and that’s what places like Atwood’s are.

Tickets for Charlie’s show are here. You can download some of his albums here.